Methods

To start, we used an existing language synthesis architecture that works on a character-by-character basis. This model is fed a large body of existing text, and it learns the probability that a character will come next, given the 40 previous ones. In this way, it can learn the relationships between letters, punctuation, even emojis, to generate correct words and sometimes sentences.

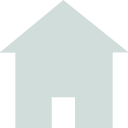

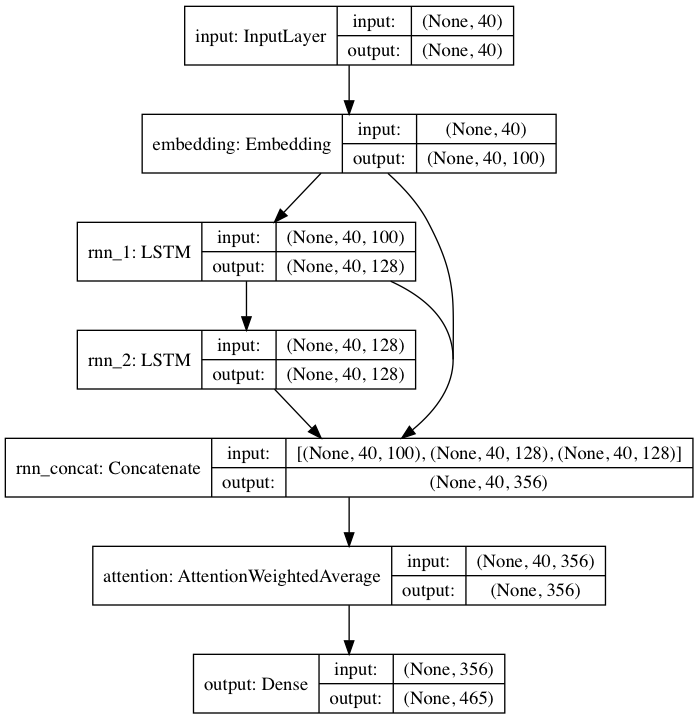

The highest layer of the network represents the characters in high-dimensional space (the embedding layer). Those embeddings are then fed through two LSTM (Long Short Term Memory) layers, which allow the network to learn which bits of information contained in a sequence are important to remember. For example, remembering that the word ‘the’ appeared might be important grammatically, but it carries very little semantic meaning. The word ‘summer’ however, would likely reflect the theme of a sentence and would be remembered during the entire encoding process.

The attention layer then takes information from both LSTM layers and the original embedding layer. This allows the model to make its final predictions based not just on recently-inputted characters but also on the information stored about previous characters, which is stored in the LSTM cells. The network ultimately returns the probabilities for each of up to 465 different characters.

Additionally, the network takes in a temperature value, which makes the network more or less confident in its predictions. A lower temperature value will produce more conservative (but also more bland and repetitive) results, whereas texts generated with a higher temperature will be more complicated, but will also contain more spelling and grammatical errors. We found that the best temperature was between .7 and .9, which made the network take some risks while for the most part maintaining good spelling and structure.

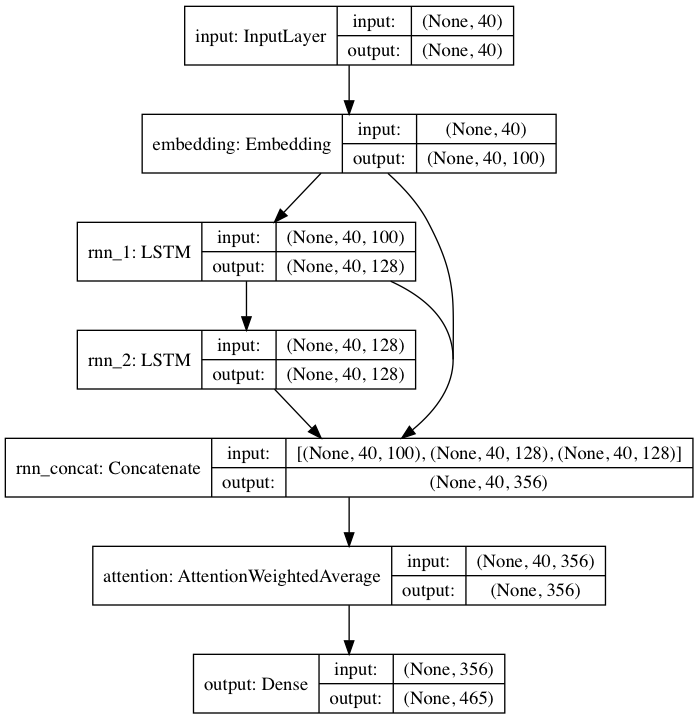

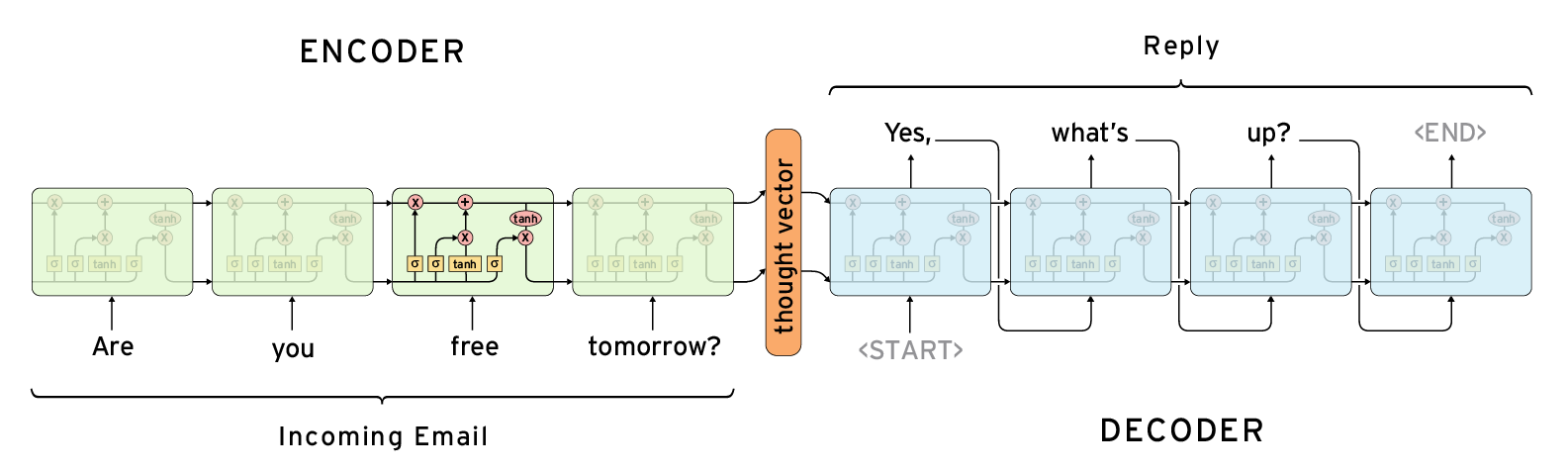

Out character model is based on the works of Max Woolf (https://github.com/minimaxir/textgenrnn) and Andrej Karpathy (https://github.com/karpathy/char-rnn) Hoping to improve the consistency and coherence of generated messages, we decided to begin generating a whole word at a time, rather than single characters. We discovered a technique that is commonly used in machine translation problems, but that can be used for any type of data with varying input and output sizes, called sequence to sequence (seq2seq). A seq2seq model has three main parts, an encoder, an intermediate thought vector, and a decoder. The encoder takes a single part of the sequence at a time (in our case a single word) to ultimately generate a “thought vector,” which is a representation of all of the words that were fed in. The model that we used implemented LSTM cells, which as mentioned earlier allow it to retain only the most important information over time Once the thought vector is generated, it is passed on to a decoder, which is essentially the opposite of the encoder. It generates a single word at a time and then feeds the previous output in as input (See figure). In this way, it can start with a broad idea and work out the specifics as it generates the new sequence.

Because this model works on a word by word basis, it does not need to learn how to spell and consequently needs less time to be able to reproduce the broader structure of emails or text messages. It is also better at creating grammatically correct sentences, because, again, it is working with larger building blocks: words. We trained our sequence to sequence model using the official tensorflow neural machine translation examples found at https://github.com/tensorflow/nmt

Out character model is based on the works of Max Woolf (https://github.com/minimaxir/textgenrnn) and Andrej Karpathy (https://github.com/karpathy/char-rnn) Hoping to improve the consistency and coherence of generated messages, we decided to begin generating a whole word at a time, rather than single characters. We discovered a technique that is commonly used in machine translation problems, but that can be used for any type of data with varying input and output sizes, called sequence to sequence (seq2seq). A seq2seq model has three main parts, an encoder, an intermediate thought vector, and a decoder. The encoder takes a single part of the sequence at a time (in our case a single word) to ultimately generate a “thought vector,” which is a representation of all of the words that were fed in. The model that we used implemented LSTM cells, which as mentioned earlier allow it to retain only the most important information over time Once the thought vector is generated, it is passed on to a decoder, which is essentially the opposite of the encoder. It generates a single word at a time and then feeds the previous output in as input (See figure). In this way, it can start with a broad idea and work out the specifics as it generates the new sequence.

Because this model works on a word by word basis, it does not need to learn how to spell and consequently needs less time to be able to reproduce the broader structure of emails or text messages. It is also better at creating grammatically correct sentences, because, again, it is working with larger building blocks: words. We trained our sequence to sequence model using the official tensorflow neural machine translation examples found at https://github.com/tensorflow/nmt